The use of the voice is a matter of course for people today. Complex processes between breathing, muscle play in the larynx and the body as a whole, between inner and outer posture - still not fully explored by science - are used by us to correspond to the different everyday situations in the form of vocal sound expression. However, the development of our vocal apparatus required many millions of years. Whether the "prehistoric men" Toumai, Orronin or Lucy1 were capable of a differentiated vocalization or even language will hardly ever be reconstructed. It is certain that for such a complex system, as it represents our language, the upright walk was necessary in any case.

Primary function of the vocal tract

This function of our nasal, oral and pharyngeal cavities, which is of primary importance in developmental history, has always guaranteed human survival by enabling breathing, eating and drinking in an orderly and coordinated manner. A human being would certainly quickly notice that a non-coordination between breathing and swallowing can have life-threatening consequences in a flash. "Swallowing" on a large piece of food can lead to immediate death due to an obstruction (blockage) of the airway. This phenomenon, now known as bolus death, occurs instantaneously, unlike choking. If the foreign body cannot be coughed up, vagal3 irritation of the pharynx or larynx leads to reflex cardiac arrest and circulatory failure.

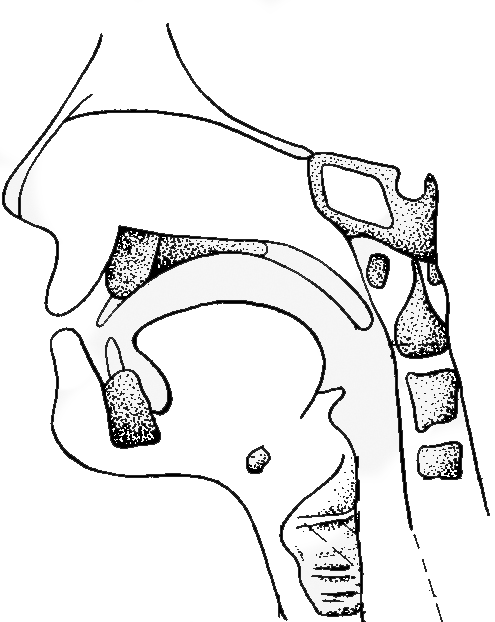

The primary function of the vocal tract is as a respiratory and food pathway. The air breathed is purified and warmed as it passes through the upper respiratory tract, which consists of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx. In the pharynx, the respiratory tract crosses with the digestive tract, which begins at the mouth opening and passes through the pharynx into the esophagus. In the act of swallowing, the laryngeal inlet is closed by the epiglottis; in addition, the vocal folds close, protecting the trachea from the entry of foreign bodies.

This function of our nasal, oral and pharyngeal cavities, which is of primary importance in developmental history, has always guaranteed human survival by enabling breathing, eating and drinking in an orderly and coordinated manner. A human being would certainly quickly notice that a non-coordination between breathing and swallowing can have life-threatening consequences in a flash. "Swallowing" on a large piece of food can lead to immediate death due to an obstruction (occlusion) of the airway. The phenomenon now known as bolus death occurs immediately, unlike choking. If the foreign body cannot be coughed up, vagal3 irritation of the pharynx or larynx leads to reflex cardiac arrest and circulatory failure.

In infants, the situation is different in this respect during the first months of their lives: The larynx is still located in the upper pharynx, which ensures simultaneous breathing and swallowing during drinking. Only after a few months does this change. Between the 5th and 7th month of life, the first teeth erupt and parents are recommended to start feeding porridge at the earliest from the 6th month of life. At this stage - most children can already sit by then - the child's larynx gradually lowers. Breath-swallow coordination is now possible and also necessary.

Secondary function of the vocal tract

The secondary function is that of a resonator and articulation instrument. Through the resonant function of the vocal tract, the primary sound that originated in the larynx undergoes a change. Movements of the muscles4 change the resonance conditions (vowels and timbre) or, in interaction with the breath, produce characteristic sounds (consonants) that are voiced or unvoiced depending on the simultaneous involvement of vocal fold vibration.

The secondary function of the vocal tract - voice, in the form of vocalization, song or speech - has evolved evolutionarily only with the erection of primates. Possibly in order to meet the requirements of living together in hordes or communities - the need and requirement to communicate with each other. Japanese researchers speak in relation to the lowering of the larynx of a two-stage model and question thereby the past models for the evolution of the language. As stage I they call the relative lowering of the larynx to the hyoid bone. Stage II is seen as the lowering of the hyoid bone relative to the jaw and the base of the skull. The results on chimpanzee infants studied by them within the first three years of life suggest that the altered laryngeal position (stage I) may have already existed before the phylogenetic lineages of humans and chimpanzees separated.6 Stage II, the lowering of the hyoid bone, may then have been restricted to the precursors of Homo sapiens. Apparently, this biological peculiarity eventually led to the emergence of complex vocalization.

Secondary function versus primary function

Our body has known both functions of the vocal tract for millions of years. They are internalized, stored in our code. Opening and closing within the vocal tract occurs spontaneously and often reflexively. I open to breathe, eat, or communicate through my voice. I close to swallow, to silence, or to protect myself. For the process of voice development, it is essential to visualize these processes as events that may be difficult to control. For both teacher and student will always experience surprises here. On the one hand, the development of vocal-personal abilities is about opening up, becoming permeable and increasing the vibrational capacity of the entire human system. On the other hand, we repeatedly find spontaneous reactions of the body that lead to a closure, a withdrawal or stagnation. And this retention of expressive energy can happen on different levels. On the laryngeal level, in the area of the throat, the tongue, the jaw, the lips, the entire muscular system, the breathing or the energetic potential of a person. As a voice coach, I can often observe the following: I practice jaw opening exercises with a student and notice that the more the jaw opens, the more the student retracts the tongue. If I call attention to this, I hear that this happens automatically. That's exactly right, because such a situation means nothing other than a victory of the primary function. Opening versus closing. Here, two systems are at loggerheads. The cultivated system of artistic onomatopoeia, which requires opening to a great extent and on various levels, is fighting, as it were, against the original, the primitive system of the need for protection. And the singing person is often helplessly at the mercy of this "battle of the giants", not knowing what is happening, how and why. The physical reactions of closing can of course also be seen as the result of a psychological "emergency situation". The fear of an approaching performance often leads to the feeling that the voice is not functioning properly. And it is not uncommon for non-routinized singers to contract the flu or a sore throat a few days before the performance. This is a somatic reaction to a psychological situation of insecurity or fear. The body regulates this very intelligently, after all it has internalized it, stored it in its code - even if it is not at all convenient for the person concerned at such a moment. Even in classroom situations, teachers hear from their students all the time, "I can always sing or play those pieces at home." So even in the classroom, students can be confronted with their anxiety. The resulting need for protection allows the voice or body to act only in a limited way, sometimes not at all. I know some people who have decided against a career as a professional musician (singer or instrumentalist) because of such a situation.

The vocal tract

The vocal tractThus, taming the primary function, controlling the recurrent closure of the vocal tract and giving up the associated need for protection, requires a careful approach if one wants to make the openings sustainably available when singing. However, this requires more than just training throat skills. An understanding of the closing and an acceptance of these processes as part of being human can lead to a corresponding cautiousness in dealing with these mechanisms. Every human being has a need for protection. And a student will not take the step of leaving the "safe terrain" reached by closure by being asked by the teacher to "loosen up a bit". To illustrate this, here are two examples.

Veronika

had dropped out of her training at the conservatory. According to her own statements, she did not get along well with the methods and teachers, and by deciding to quit she had also avoided the stress that the approaching exams would have brought. We progressed well and quickly, and Veronika regained her love for music and singing. Over time, I noticed a dynamic in her behavior during certain teaching situations. Whenever something new appeared in Veronika's voice that I wanted to pursue with interest, she blocked, tried various side paths, argued, and became aggressive. Sometimes this reaction showed an intensity that could even lead to her voice "breaking away" or to signs of hoarseness. And again and again Veronika was on the verge of quitting the class. In each case, she had experienced newness as something threatening, snatching away her securities. "It's as if my truth is being stolen from me and replaced by nothing," she described the intensity of the surges of emotion in her body. And in order to escape what was apparently standing there threatening her in each case, she inevitably had to try to save her skin. Veronika learned to voluntarily give up her securities and to see this process as temporarily necessary for the development of the voice.

Alexander

had a beautiful and powerful voice. His start as a tenor in the musical field was successful. However, he was troubled by the fact that his voice could change from one moment to the next. He had the feeling of not being able to find security, of not being able to rely on his voice. It is true that there were moments or even days when everything went completely smoothly. However, it could happen that his voice completely failed at the mere thought of a performance or casting situation. So Alexander devised a strange training program. He tried to "steel" his voice. The musculature was to be trained by constantly singing loudly in such a way that it would be ready for an emergency. A difficult situation. Sometimes he sang so loudly that I assumed one of my neighbors would soon pick up the phone to file a complaint with the police about noise pollution. And when I occasionally asked why it had to be so loud, I usually got the answer, "Well, because it's going!" The interesting thing, however, was that Alexander showed no signs of vocal fatigue from his loud singing. He loved this rush of his own power, and accordingly he felt ready for the stage. Stupidly, however, it could happen that this feeling turned into the opposite the very next day - and accordingly also his vocal and musical performances. Alexander's voice then became unstable. He could not preserve the brilliance and radiance for the next day, and he suffered accordingly. The situation repeatedly triggered psychological crises in him. Again and again the same questions arose in him: "Will it work?" And, "What will I do if the theater takes me?" He found no answers within himself. Instead, chasms opened up beneath him. He finally realized that the vocal power and volume he used were representative of authority and security. His father had died at a very early age, and consequently he had been denied paternal support. He wanted to shorten the development towards a self-responsible personality by functioning at peak performance. However, his body showed him again and again that the way to go this way needed a correction. Alexander finally sought professional psychological help. He took leave of singing for a while and found a new, gentler and more loving approach to himself. Inevitably, his voice benefited. It could come and go, was no longer forced to stay. As a result, she was happy to stay longer - voluntarily.